|

I |

n

1986, when massive streets protests drove Ferdinand E. Marcos away from Malacañang Palace, the official

residence of the Philippine president, Chavit Singson was Provincial Governor

of Ilocos Sur and Erap Estrada was Municipal Mayor of San Juan, Metro Manila.

Both Chavit and Erap, who had been friends for close to two decades by then,

swore to each other to remain in their respective posts when Cory Aquino, the

“housewife” who succeeded Marcos as President, began swatting away the

incumbent elective local officials, like political flies, throughout the

country.

“They

are freeloaders,” said Aquilino “Nene” Pimentel, Jr., the new Local Government

Secretary of the Cory Aquino government, in reference to the “overstaying”

officials.

“Hindi tayo bababa sa pwesto,” Erap

assured Chavit over a glass of whiskey.

“Over

my dead body, pare” Chavit replied.

After

two weeks, Erap relinquished his post, and Chavit did the same after another

two weeks. There was no bloodshed, either in San Juan or in Ilocos Sur.

Erap

went on to become a Senator a year later. Chavit reclaimed his seat at the

Ilocos Sur Provincial Capitol in 1988.

Erap’s

election to the Philippine Senate in 1987 was eye-catching. He was the lone

survivor among opposition senatorial candidates. None of his party mates could

quite withstand the “Cory Magic” like he did. At that time Cory was so popular

that, pundits chuckled, her endorsement could make even a dog win in an

election.

In

the Senate, Erap liked to trip Nene, a fellow neophyte senator, on the floor

whenever there was an opportunity for it.

“Would

the distinguished gentleman from San Juan yield to a few clarificatory

questions?”

With

that standard line, Nene opened his interpellation of Erap (sponsoring his pet Kalabaw Bill).

“With

pleasure, Your Honor,” also a standard line. But Erap would add a novelty: “And

thank you for removing me from my post in San Juan, my being jobless forced me

to to run for the Senate.”

But

being member of an exclusive 24-member club melted the icy-cold alibi of

distance. Being senator had its feel-good effect. Lots of it. Probably good

enough for one to see value in the other. In time Erap and Nene became mag-kumpadre and, from the looks of it,

perhaps friends.

“The

President was kind enough to invite me as one of the sponsors in Jinggoy’s

wedding,” Nene recalled. Jinggoy, Erap’s son with wife Loi and who would also

rise to become senator, wed Precy Vitug in 1989. (Among Roman Catholic church

members in the Philippines—who constitute around 80 percent of the

population—being a sponsor in at least three of seven sacraments of the faith,

such as marriage or matrimony, entitles one the privilege of being kumpadre (male) or kumadre (female) of the parents receiving the sacrament.)

“I

returned the compliment when Koko,” Nene’s son, and now also a senator, “wed

Jewel Lobaton, a former Miss Binibining

Pilipinas Universe titleholder, in January 2000 with Erap as principal

sponsor,” Nene said.

When

Erap became president, media played up an anecdote about Nene’s “No ID, No

Entry” experience at the Palace. The senator was subjected to a rigid security

check by the presidential guards. Nene felt slighted by the treatment. “But

except for that small incident,” he said, “I have no complaints about the

President.”

Erap

explained that in his administration, the rules equally applied to everybody,

whether they were messengers or senators. After all he promised in his

inaugural speech that friendship and kinship would not influence his official

functions. Getting through the palace gates had never been easy—something which

Erap highlighted in his plunder trial 4 years later to bring home the point

that jueteng collectors could not

just freely see him in office, much less deliver to him bundles upon bundles of

jueteng money. Of course, after a

while, the members of the so-called “Midnight Cabinet” who freely roamed the

palace grounds at nighttime would also become public knowledge.

But

let’s not move too fast. Let’s get back to when his political star was still on

the rise.

It

was easy to say Erap had his own political magic. Adored by the Filipino

masses, the lone oppositionist in the Senate had likewise attracted allies from

outside the supposedly “dumb masa”—as

former Supreme Court Justice Isagani Cruz called it—social class. One of them

was colleague Orly Mercado, another Cory-backed senator. Together, they quietly

started plotting Erap’s way to the top. An emerging two-member political party

got around to casting and re-casting its tentative shapes.

The

Erap-Orly political semen eventually sired the birth of Partido ng Masang Pilipino, or PMP.

In

1990, the PMP had 2 members. In 1991, it had 21 members. In 1992, it bagged the

second highest office in the Philippines.

Fielding

Erap as candidate for Vice President in that year’s national elections, the PMP

rose to become a socio-political magnet and its lead character having earned

the tag of “Cinderalla of Philippine politics,” as a Philippine newspaper

editorial put it. He won the vice presidency. He was on his way to the top.

Eddie

Ramos—FVR to many—Cory’s trusted Armed Forces Chief of Staff and later National

Defense Secretary, succeeded her at the throne.

Like

many of those who comprised the “schooled” segment of Philippine population,

Eddie was not fond of Erap, but both being choices of the electorate, FVR had

to co-exist with the Vice President. He proceeded to create a customized office

for Erap.

And

so it happened that, from 1992 to 1997, Erap was Chairman of the Presidential

Anti-Crime Commission (PACC). Erap came to be known as anti-crime czar. He

found lots of action in the job and relished it, although he hardly showed the

same level of enthusiasm when it was time to break down issues of national

interest.

In

a letter to Philippine Daily Inquirer editors, Nick Lagustan, then FVR’s

spokesman, said: “Vice President Estrada attended most of the (cabinet)

meetings, even if he habitually left the Cabinet Room well before adjournment,

leaving his chief of staff, Robert Aventajado, to take notes.”

From

the image he developed in the movies as champion of the oppressed and refuge of

the downtrodden, Erap seamlessly transitioned to being the real deal, one who

was on top of restoring order in the crime-infested streets of Manila.

And,

as in the movies, this role needed a supporting cast.

At

PACC, Erap put together an elite team of law enforcers led by now senator

Panfilo “Ping” Lacson. Referred to by his band of operatives as “71”—being a

member, along with fellow senator Gringo Honasan, of class 1971 of the

Philippine Military Academy, Ping had a solid account of his work in the field.

He

had been a Philippine National Police (PNP) Provincial Director since 1988

(with stints in the provinces of Isabela, Cebu and a few months in Laguna). “I

gladly accepted the offer to join PACC since I was not happy anyway with my

Laguna assignment,” Ping said in a 2009 speech delivered on the Senate floor.

Nevertheless,

the urge to look good had put the life and limb of otherwise innocent

by-standers at risk. Barely a month in their posts, PACCmen murdered Elmer and

Jeffrey Pueda, Luis Matro and Leonardo Montalvo, according to a congressional

report.

Three

months later, PACCmen—having bungled a rescue attempt involving two kidnap

victims (scions of wealthy Filipino-Chinese families) in which Galicia gang

members, the suspected kidnappers, killed the victims, and pressed to make

amends with the shocked and hurt Filipino-Chinese community—hunted down in

Batangas the perpetrators, only to bungle it one more time when they tagged the

wrong man, erroneously killing Wilfredo Aala, an overseas contract worker.

PACC

also matched the methods of criminals. If the Galicia gang could kill two youngsters

to get what they wanted, PACCmen—and specifically Ping—could cause the death of

a mother and her child to force innocent people to reveal information, if

Jinggoy and Kit Mateo, one of Ping’s former aides, were to be believed.

In

2009, Jinggoy released a video of the bed-consigned Kit Mateo—gasping with his

last few breaths—in which he said (and as reported by ABS CBN News.com) that

“Lacson … ordered the murders of a … woman and her 8-year-old daughter by

throwing them out of a helicopter, which was flying near Corregidor Island. He

said the two were relatives of then Red Scorpion Gang leader Joey de Leon and

were killed after they refused to tell Lacson the whereabouts of de Leon.”

In

1995 PACC figured in a major controversy. Its operatives gunned down 11

suspected criminals in what official records said was a “shootout.” Subsequent

investigations, however, including the one conducted by the Philippine Senate,

have raised the possibility that the casualties were victims of “rubout” rather

than shootout.

Despite

suspicions that PACC was taking shortcuts in dealing with suspected criminals,

Ping became the new darling of a crime-weary public, especially when his

operatives killed Joey de Leon, the reported leader of the dreaded and

notorious Red Scorpion gang. This bandit reportedly victimized with alarming

regularity wealthy Filipino Chinese businessmen.

No

wonder Ping would soon be the toast of the Chinese community in the

Philippines. His boss, Erap, the Vice President, basked in the limelight even

more.

Although

Erap, as crime-czar, had been criminally charged for the death of a number of

people, some of which were PACC’s victims of either mistaken identity or

summary executions, people in general did not care. For one, he was too popular

to be trashed by public opinion. For another, Ping and his PACCmen were seen,

as one gang leaders fell one after the other, as putting their lives on the

line in the service of peace and order. And still for another, the criminal

cases against Erap were settled out of court as soon as they were filed, using,

in some instances, private funds.

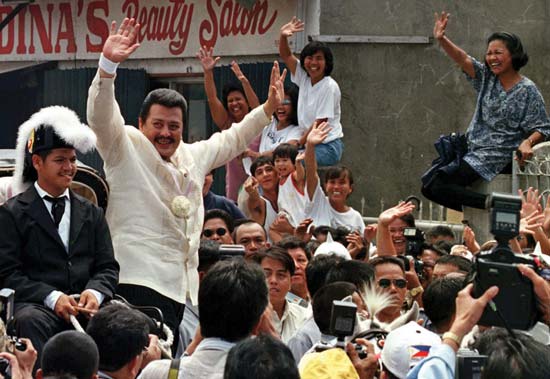

Erap

ran away with the win as Presidential candidate in the 1998 elections. He

received 43 percent of the total vote. Up to that point, no other presidential

candidate has enjoyed such an overwhelming mandate.

No comments:

Post a Comment